How did you discover the niche of public speaking? How did you know it was what you wanted to do, and what are you most excited to speak about?

Ever since I was diagnosed with autism at 13 years old, I began speaking to multiple audiences about autism ranging from my fellow students to police officers. I spoke to the students on my own and my mother accompanied me during the talks to the police officers. At first, I didn’t really enjoy nor understand the purpose of talking to police officers. I felt like a puppet or someone my mother felt she had to show off in order for others to understand me and other people with autism. As I grew up though, I began to understand that I was making a difference in people’s lives and people were praising me for it and appreciating what I was doing. This was a wonderful feeling that stayed in the back of my head as I progressed through my career in accounting. I continued to do some speeches on the side while working in accounting until I found myself growing increasingly unhappy with accounting and my peers growing increasingly unhappy with their lives. This caused me to take a leap of faith and leave my accounting career behind including a permanent job with benefits to tell my story, what I’ve learned along the way and why all young people, with and without learning differences such as autism, need to know themselves, love themselves and be themselves if they are to become their best selves! This process of self-discovery is what I’m most excited to talk about and is what is most needed in the lives of young people with autism.

Your website mentions that you are proud to have accomplished many of your life goals (driving, full-time employment, living independently, and having a girlfriend). Which of these goals did you find the hardest to achieve, and what were the main factors in helping you reach it?

Of all of my accomplishments, obtaining permanent, gainful employment was and in some ways continues to be my most difficult goal to achieve. From the time I was in high school, I had my sights set on being George Lucas’s accountant because I was good with numbers and loved Star Wars. I told my mother about my dream and, rather than dismiss it, she told me what I had to do. “You want to be George Lucas’s accountant? You need to take college courses, pass advanced tests, get jobs in the entertainment industry, etc.” Rather than quit at that moment, having a Batman mentality of not giving up and remaining disciplined in my approach, I saw my journey through to becoming a certified public accountant (CPA) taking the necessary courses, passing the tests and holding a number of jobs in entertainment-related companies. These companies included but were not limited to Hollywood Video, Blockbuster Video, Regal Entertainment Group, Universal Music Group and The Walt Disney Company (which acquired Lucasfilm after I left the company so retroactively and indirectly…I accomplished my goal of being George Lucas’s accountant!!! It’s a matter of perspective and how you see your circumstances that determine your success!). I was very fortunate to be able to explore my options and get exposure to so many different companies, to gain experience from each of these jobs, which I knew nobody could take away from me even if I lost a job, and I could pursue more of what I wanted and pursue less of what I didn’t want so I could evolve and take my life to the next level. This allowed me to move my life onward and upward and not let rejection or failure get me down. Why? Because rejection and failure are part of life and help you get to where you truly belong and fit in (your niche)!

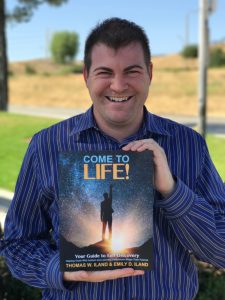

Why did you write Come to Life! Your Guide to Self-Discovery? What is your hope for its audience?

Employment

When I started college, I discovered that life doesn’t come to me…it’s up to me to COME TO LIFE! This is why we named the book “Come to Life!” My mother and I have found that the process of self-discovery (my mantra…”Know Yourself. Love Yourself. Be Yourself.”) is being left out of transition plans and other future planning in youth with autism in particular. When parents, advocates, etc. ask someone with autism what he/she wants, where he/she sees him/herself in five years, what he/she is good at, often times the response is “I don’t know.” At that point, parents and advocates start guessing and put the young person on a path to a life that he/she doesn’t want. When that happens, the young person’s future becomes compromised because they’re living a life that is essentially not theirs and that is causing the anxiety, depression, hopelessness, crashing and burning, etc. that so many with autism, particularly adults, are experiencing on a daily basis. That said, all efforts must be made to help the young person live the life he/she wants for him/herself as opposed to changing the person to live the life others want for him/her. The steps to making this happen are outlined in Come to Life! and I hope that readers, namely people with autism and other learning differences, will be empowered and hopeful that they can and will have a say in their future and, with their team of parents, advocates, therapists, etc. can create the life they want for themselves.

What suggestions do you have for parents who are worried about their child having stressful and/or escalating interactions with law enforcement?

First and foremost, my mother and I have learned based on years of training thousands of police officers that just training the police about autism is not enough anymore. Young people also need to learn what to expect from and how to interact safely with the police. For parents worried about their child having poor interactions with law enforcement, I highly recommend the parents invest in Be Safe: The Movie (available at www.besafethemovie.com). Telling isn’t teaching so this video-modeling curriculum SHOWS young people how to interact safely with police. When it comes to interacting with police and other first responders, the four problematic areas for young people with autism are:

Reaching into their own pocket without being told to (which officers can mistake for a weapon)

Safety is currently being left to chance when parents wrongfully assume their child won’t ever have an interaction with law enforcement, that the child will know what to do in such a situation or that a nonverbal child is unable to learn how to follow instructions, for instance. Be Safe is tailored to all verbal and cognitive levels and only positive examples are shown to viewers so as to not create confusion and in order for a movie of what to do and how to behave to be playing in young people’s heads when they meet the police. The movie also reframes the instructions to more positive ones such as “Stay where you are” as opposed to “Don’t run” or “Stay calm” as opposed “Don’t panic.” This is a much more effective approach and it has actually saved lives and resulted in better interaction among young people and law enforcement.

Have you ever been in any danger because of misunderstandings among law enforcement about autism? Or someone you know? What are the real dangers parents and individuals on the spectrum should be aware of?

I have had my fair share of interactions with law enforcement, none of which have escalated to the point of detainment, arrest or imprisonment. One time I got pulled over and thought to myself, “The officer wants to see my ID” and proceeded to reach into my pocket without the officer knowing it. The officer approached my car and told me to keep my hands on the steering wheel we he could see them. Thankfully, he requested this of me instead of pulling out his gun and shooting me, otherwise I wouldn’t be talking to you right now.

My mother and I have many horror stories of young people with autism that we know ending up on the wrong side of the law. For instance, here in California, an 8-year-old boy with autism was pulled from his classroom by law enforcement without his parents’ or the principal’s knowledge, was then interrogated by police without an adult present and proceeded to confess to a crime on tape.

Another situation involved a young man with autism being pulled over and was asked by the officer if he was on drugs. The young man had just come from a drugstore where he had bought vitamins. Thinking that the vitamins were drugs since they came from a drugstore, the young man responded, “Yes, I’m on drugs.”

Another young man was given the field sobriety test (FST) where he had to walk a straight line, but due to lack of physical balance due to brain lesions he had, he couldn’t walk the line. As a result, the young man was arrested, taken to jail and handcuffed to a bench while he waited for his blood test results to be available the following morning.

I have more stories, but these are select and primary examples of young people with autism and other learning differences not knowing what to do, taking an unfamiliar situation or question out of context, not knowing their rights (to remain silent, to an attorney and other protections against their own self-incrimination) and not self-disclosing their diagnosis (whether they know about it or not) to police, watch commanders, etc. This is why training the police is no longer enough and why young people need to be educated, too.

Your website mentions you are on the Board of Directors at Autism Speaks. What do you say to other advocates on the spectrum who disapprove of the organization and its aims?

For anyone that might disapprove of Autism Speaks or me being on the Southern California chapter’s board of directors, I say to them that first impressions, while powerful and often difficult to undo, are not always correct. The organization is currently taking approaches to move away from the idea that autism is something to be removed and cured and more towards the idea that autism is something to be acknowledged and accepted. It’s never too late to seek redemption and the best way to foster change in an organization is from within rather than from the outside. That is why I have joined the board in order to create change within the organization and how the organization better serves its end users across the entire lifespan.

In addition, speaking from experience, I know that holding grudges against people and organizations for their past mistakes only hurts the person holding the grudge and could hinder his/her progress. When that hatred, anger, intolerance and resentment turn inward or aren’t released in a healthy way, the person risks not truly loving him/herself to his/her full capacity. Also, shutting out a person or an organization due to false pretenses or wrong impressions can be a great disservice to someone after saying “no” to people, resources, ideas, etc. that can help a person live his/her best life and be his/her best self. I have gotten to where I am today because I have a team of people with me as opposed to going it alone AND I have kept an open mind rather than being closed off to those I do not necessarily agree with.

In conclusion, this mindset of listening to others and hearing their opinions, suggestions and considerations is critical to success. Stephen Covey’s fifth habit of highly effective people states, “Seek first to understand and then to be understood.” When people with autism are so desperate for the latter, they often discount or dismiss the former. I encourage people with autism, as difficult as it might be given their diagnosis, circumstances, etc., to listen to what others like Autism Speaks have to say, gather all the facts needed to make an informed decision, weigh the positives (pros) and the not-so-positives (cons) of the situation and then decide how to proceed. At the end of the day, we all have autism and share the same needs which is why a unified front, rather than a divided front, is more critical than ever.

What mistakes do neurotypical autism advocates make?

Once again, in my experience, I have found that autism advocates that do not have autism can and do make some fundamental mistakes along the way. It began with my mother. I was her first child and she was in denial at the notion that I may have autism when her sister, the autism specialist for the State of Illinois, brought it to her attention when I was four years old that I may have autism. At the time, the writers of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) deemed that I couldn’t have autism since I didn’t have an intellectual disability. It wasn’t until I was 12 or 13 years old that the DSM definition of autism changed and I then fit the criteria for an autism diagnosis. I couldn’t accept my diagnosis until I knew my mother had. Once we both accepted it, we became a unified front and started creating the change we wanted to see for ourselves and others.

Many autism advocates that don’t have autism think they know what’s best for people with autism. This is only somewhat true though. Advocates have good intentions and they should; however, they cannot live the life of the person with autism…only the person with autism can do that. When advocates get too clingy or coddle their young person for too long (whether it be underestimating the young person’s potential, letting fear be the main motivator behind decisions, or having an undying need to be right, just to name a few), it hinders the progress of the young person or, in some cases, can even result in learned helplessness for the young person. As mentioned in Question #3 above, the focus needs to be on helping the young person live the life he/she wants for him/herself (and first finding out what that is first) as opposed to changing the young person to live the life others want for him/her. By making the young person’s goals the focus of the support and services he/she is receiving, the young person has a better likelihood of understanding WHY they are getting the help they’re getting and this will yield a better outcome for all involved.

I also believe it’s critical that adult advocates without autism acknowledge their mistakes and that they didn’t always get it right. This opens the possibility for forgiveness both from the person with autism and for the adult advocate him/herself. For a long time, I thought I had to be perfect because I thought my mother was perfect. When she explained that she wasn’t, I began to see that I could make mistakes and still be all right and still learn from them. I have also forgiven my mother for the years of denial and for masking my areas of need. I understand that she was doing the best she could and that those efforts have helped make me into the man that I am today. You’d be amazed how much the words “I’m sorry” and “I love you no matter what” can mean to someone with autism.